All Shook Up

How a friendship kickstarted my life the day Elvis died

I beg to differ with Aristotle. The friend is not just a mirror-self. Friendship is not the perpetual repeat of two samenesses. That would not explain that it can really shake you up, that friendship can generate a whole new life. For the very same reason it can really shake you up when it dies. But what follows is not about dying. Quite the opposite.

Age 12: do or die

Forgive the dramatic beginning, but it’s probably not all that unusual for kids around that age to ponder the possibility of a premature afterlife. So, no trigger warning here but a disclaimer instead: pathos pushed out to the margins has a habit of squeezing itself back in between the spaces, gets particularly viscous when you mix nostalgia with friendship. Every time you manage to scrape it back out to the sides, you realise that underneath is just ordinariness.

I have loved music ever since I can remember. One of my earliest memories is about playing a tiny plastic saxophone, plastic trumpet-playing friend by my side, at one of the weekly rehearsals held by the local brass band. Its venerable members, variously gifted, unevenly enthusiastic, but united by a shared loathing of all things pianissimo and harmonious, pumped their miners’ lungs (or what was left of them) hard enough to drown out our screeching and make us feel like it was us who were making the music.

I had just turned 12 when dad woke me up late one night. Not unusually, he seemed a little drunk, his clothes and hair tobacco-soaked. He put a small case on my bed and I immediately knew what it contained. Dad had been repairing instruments, including clarinets, and I loved the filigrane fragility of the silver keys on black wood I had never been allowed to touch until that night. Musical instruments are sacred. And besides there was this guy in town who was the Real Deal. His clarinet tone was like butter on warm toast. I wanted that too.

Soon after I began to take lessons from the local tailor who was also the church choirmaster. He played the church organ and the tuba, had dabbled in clarinet in his younger years, and knew something about music theory. I think my dad asked him to teach me because the Real Deal wouldn’t teach anyone, although to his everlasting credit he was the person who showed me how to turn squeak to sound, sour milk to something more like yoghurt. (And in any case, we spent his last years as friends playing saxophone duets whenever I visited the Old Town.)

Not half a year later I was asked to play at Midnight Mass. That was a BIG deal. Just about the whole town was going to be there—atheists, agnostics, alcoholics, three little old church mice, my dear uncle with the sonorous bass vocals, bane to every priest who dared go beyond the 5 minutes he allotted to their sermons, and possibly other members of my clan. I was chosen to replace an older kid who’d held the 1st clarinet chair the previous couple of years, but had given up on music. Which was a pity by the way, because he was a damn fine clarinetist. Or at least he had tons of promise. Or maybe I just liked the corny tunes he used to play around the camp fire.

I still remember the name of the mass we rehearsed that night. It was the Wieser Bauernmesse — a Peasant Mass from a place called Wies — though I’ve never been able to find it anywhere ever again. I can even hear parts of it still in my head some 45 years later.

What I remember most of all about that rehearsal night is the scowl of the choirmaster’s wife whose angelic alto did nothing to veil her disdain for the skinny kid trying to make his way through the Credo in A major. (For the musically literate: that would be B major for Bb clarinet. Five sharps in a culture that only really knew one or two B-flats, but knew those real well). Muttering into her double chin, openly complaining to her husband, shaking her head every time I put reed to lip, that stern matron seemed to grow in stature with every bar. Finally her shadow drowned me out.

There is a creek running through my old town. After a few days rain it too grows in stature. Two bridges lead across it. On the way home that night I looked down from one of them, and not to spy on trout. I waited just long enough for cowardice to win out.

But why? Being disrespected in front of a bunch of people who couldn’t have cared less surely isn’t a good enough reason—if there ever is one—for a 12-year-old to even as much as contemplate oblivion.

There’s a backstory. I won’t give you all of it. Here’s just a sliver.

A-b-e-r: Austria, 1976

Not only did I love music, I loved reading, which was a little unusual for a working-class kid at that time, and it was particularly unusual at my so-called high-school, which sat in another town. That meant that I and the other kids that caught the train to school each morning were considered outsiders, foreigners, aliens.

You might find this hard to believe, but we experienced xenophobia and discrimination first hand at the hands of people who were exactly like us.

The German word Aber (but, however) rearranged my psyche that year. We were asked to pass a book around in class one morning for each to read a paragraph. I still remember the light falling on the page, and the kid’s name and face sitting next to me that day.

The first word of my paragraph stared at me. A-b-e-r. And I stared back at it. I kept staring back at it for what seemed like e-o-n-s. A void began to open up, a void filled thickly with silence. That silence enveloped me, seeped into me, and then threatened me from within from that moment on and forever.

My almost-hidden life, a kind of half-life, had begun.

The odd stammer—not unusual among some males in my family—had turned into what much, much later I learned to identify as a covert stammer. No one knew, because to keep embarrassment at bay—at that time and that place stammering was still equated with idiocy—I learned quickly, first in German and then in English, to hurl synonyms at those beast-words that would try to choke me.

I deleted them, replaced them in split-seconds with speakables, preferably with words that did not require emphasis on the second or third syllable. (Oddly. Because aber definitely requires stress on a.) You might replace, say, phenOmenon with thing, or modERnity with modern life. (You might think these are odd examples—unless you are teaching about social phenomEna and a course on Theories of ModERnity.) Or you find yourself in a tight spot every time you want to ask how your friend’s son is going, but because you can’t say his name, you keep on calling him your boy or little man or whatever catapults itself into your mind any given moment. The replacement process should ideally take <0.5 seconds for the sake of fluency-pretence, since it’s all about covert action.

Experiment! It’s fun! There are only three provisos: (1) you must play the game in the presence of others, preferably strangers or your boss; (2) imagine yourself back into your teenage self; (3) you’ve got <0.5 secondsReady? Don’t forget: First syllable good, second syllable bad, third syllable touch-and-go, fourth syllable unlikely, monosyllable best. Go!

How’d you go? You can see the pros and cons, can’t you? You get very good at acquiring a fairly extensive vocabulary, which is especially helpful when learning a new language, though not that helpful when you try to speak your original mother-tongue, because your vocab has retreated back to 1986.

But let’s face it. There are plenty of words you wouldn’t ordinarily choose if you had the choice.

It really helps if you can say what you really mean to say whenever you speak—at your leisure. Sometimes you sound downright dumb. Not because stammering itself makes you sound dumb, and not because people have a habit of finishing words for you when you do get nuked by modErnity on the odd occasion when you’re sick of modern life, but because the words that ease the delivery often hover on the line between appropriate and inappropriate, strain toward the out-of-kilterish, and in any case are very rarely better than first choice.

As a fellow ESL speaker you might be able to get away with it. But don’t forget how ESLs used to get away with stilted prose until Vladimir Nabokov came along.

But who wants to get away with it?

Back to me and my clarinet and the Midnight Mass rehearsal.

So, only a few months before that night it felt like music had given me my voice back. A voice that promised more fluidity and fluency, if of another kind. And it seemed to come from somewhere much deeper than I’d ever known. I had just glimpsed that depth as no more than a promise between the squeaks and squeals of beginner’s clarinet.

The mere sense that this too could be snatched from me, and this time at someone’s whim, would explain the long minutes I’d spent contemplating the meaning and usefulness of life on that wintery-cold night, bridge-hovering.

The gig went well. All’s good that ends well. But what if life gets better because it ends badly for someone else?

A year later Elvis died

I imagine 16 August 1977—or it could have been 17 August, considering that the news took a while to travel from the US to the Old Town—to have been a summer-warm day. I had just had lunch, and the sounds of a guitar drifted in through the window. I knew of course who it was: my best friend in my whole world, the first person I had ever really looked up to.

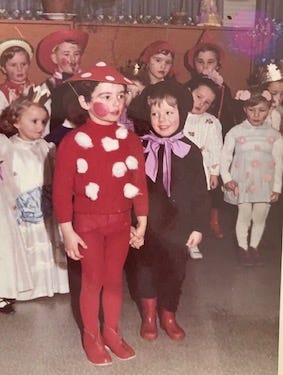

He sat on the stairs of the building next door, the old Kindergarten we both had visited and outside of which we had met 7 or 8 years earlier when he had moved from up the hill down into the valley, and he passed me and I asked him whether he wanted to be my friend and he said yes or ok and took me by the hand and we strolled on.

That’s how I imagine it, but it doesn’t really matter. What matters is the sentiment: the love only kids know for each other before mendacity, guile and self-consciousness fray us.

Check this:

As much as you might hope now to read that that day my friend sang Love me Tender or Heartbreak Hotel, he was much more likely to have tortured his guitar to an impressive rendition of Jailhouse Rock.

For he was already fiercely dedicated to Rock AND Roll.

And anyway, if he did in fact sing Love me Tender or Heartbreak Hotel it wasn’t anything to do with me, or friendship, or love or any of the heart-pains he, like most of us, had to deal with or may have dealt out later, but simply because he could make those tunes rock too.

Plus, remember: this ain’t Nashville, Tennessee, my friends. We are talking about the 8.500 foot foothills of the Central European Alps.

I on the other hand was dedicated to Austrian-like folk-like music more germane to geography and climate.

Austrian-like folk-like, because my heroes were Slovenian or Czech, and most Austrians only like music that approximates their folk music but actually isn’t. I liked those Slovenians hailing from Kranjska, not only because my dad blasted our flat with their music day and night, but because—here comes my music-theoretical retrofit—those guys littered, I mean spiked their tunes with diminished seven chords, which were as exotic to us as a good Austrian yodeller duet consisting exclusively of harmonies in Thirds might be to the average Javanese gamelan player.

Thus me: what should then that be? (lit. trans.), and he: that is Elvis. He died.

Out went the clarinet, in came the saxophone. But not before we killed some LPs listening to Elvis, Chuck Berry, Bill Haley and the Comets et al. — and formed a band called, aptly but somewhat unoriginally, The Comets.

When the saxophone arrived—a gift from my uncle who gave up playing it that day—my friend would patiently sing horn lines to me. He’d help me work out the two notes, and which finger was required to produce them. I would later growl those out as rhythmic stabs offered on my knees sporting backward-blow-dried neatly-coiffed hair, which lost me a potential first girlfriend before that potentiality had even occurred to me, to 20 perplexed attendees at the local gym, July 1977.

Imperceptibly at the time—and how could it have been otherwise?—life was beginning to turn a bend that would lead way, way beyond the shadow-casting mountains. The voice I had recently discovered, and had made up for some of what I’d felt I’d lost, was still only a fledgling voice that, for all I care today, may never have fully matured. But it got some validation first from my first and (now oldest by duration but not by age) friend, and then from others I liked, looked up to, respected, wanted to be like.

Friendship has meant the condition of possibilities for another kind of life.

There is much more to tell. But this is the gist of the beginning of it.